WAKING THE WITCH

A one-act, immersive chamber opera

When people in power believe in conspiracy theories, how do we respond?

Waking the Witch is a one-act (~75 min.), immersive chamber opera for solo countertenor, mezzo-soprano, or contralto and Pierrot ensemble that explores human vulnerability to absurd beliefs as well as the danger of mixing authority and religion with black-and-white thinking, fear of those with less power, and conspiracy theories. The audience assumes the role of an accused witch, physically surrounded with a single-minded interrogator and animal familiars of questionable reality (played by the treble instruments of the Pierrot ensemble). The libretto is derived from the words of both historical witchfinders and modern-day leaders and movements with eerily similar messaging. Listeners must consider how we might navigate the seemingly impossible logic of power lost in moral panic, while remembering the dangerous reality that these things did, and in many ways still do, happen.

The development of Waking the Witch received funding from

OPERA America’s Opera Grants for Women Composers: Discovery Grants program, supported by

the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation.

Waking the Witch is currently in the end stages of development, and is available for commissioning and premiere productions.

Please email ashikday@gmail.com with any inquiries about the opera or to receive updates.

Forces

Solo countertenor, mezzo-soprano, or contralto and Pierrot+ ensemble: flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano, and percussion (bass/kick drum, tom, woodblocks (2), tambourine, and suspended cymbal)

WITCHFINDER: Countertenor, mezzo-soprano, or contralto

ACCUSED: Audience (non-singing, non-speaking)

FAMILIARS (optionally included in staging; drawn from the Pierrot ensemble):

A BLACK MOUSE: Flute

A GRAY RABBIT: Violin

A WHITE KITTEN: Clarinet

(Optional) Surprise Chorus (SSA, 3-12 voices)

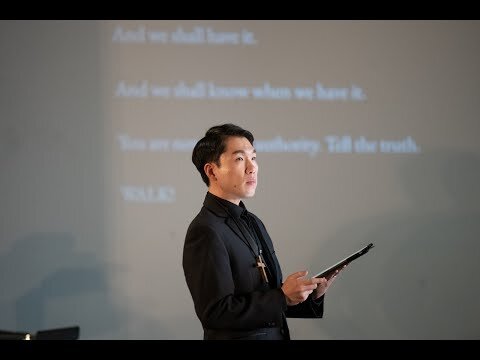

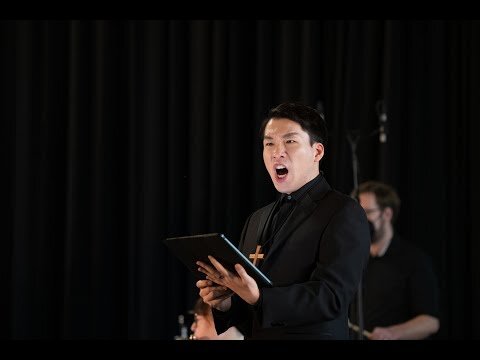

Min Sang Kim as the Witchfinder during a developmental workshop of Waking the Witch.

EXCERPTS

Watch and listen to excerpts from developmental workshops of Waking the Witch in June, 2022 (music, scenes I-V) and December, 2022 (full work, with minimal staging), held in Washington, DC. These workshops were supported by Opera America’s Discovery Grants for Women Composers.

about the opera

Synopsis: In Waking the Witch, you, the audience, find yourself in early modern Europe or the American colonies, brought before a Witchfinder. The world is tense, and people live alongside a host of constant threats. This Witchfinder might be self-appointed, but he is certainly backed by powerful men, sure of his mission, and convinced you are part of a secret cabal trying to destroy all that is godly.

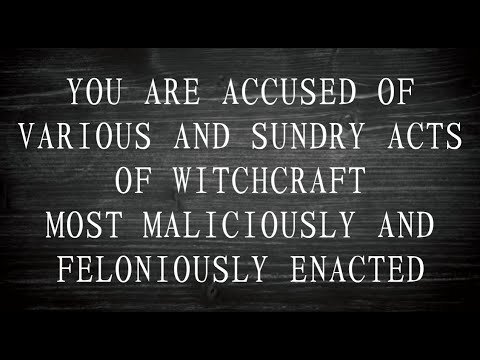

Your neighbors have accused you of various acts of maleficia, evil acts of magic that are only possible for those who’ve committed the worst of all possible sins: making a pact with the devil. The Witchfinder is prepared to fulfill the righteous duty of investigation, doing his part in stamping out this increasingly rampant heresy. He says you are to be walked: not tortured, of course, only asked to walk about this small room, this night and maybe more, without rest or sleep until the truth is discovered. The questions begin: Why does the tavern keeper visit you, and where did you get the knowledge to heal his son? Why did your neighbor’s illness start just a few days after she refused to give you alms? Why did the magistrate, his body protected by his godliness, suffer the death of livestock just weeks after you complained about him? Haven’t you been seen oddly close to small animals, a sign of owning shapeshifting demons known as familiars?

You are interrogated about this and more, though your answers matter little to the Witchfinder, who already knows what he believes. Still walking, the world getting hazy, you start to lose bits of time. You see things like animals, but they don’t seem real… or nice. The Witchfinder isn’t done: What happened when your body was searched for the devil’s mark? Did you willingly accept the devil, or were you coerced, and why didn’t you fight back? What crimes happen at the witches’ sabbath, and more importantly, who else was there? What do you say to all this which is apparent?

You are continually kept from resting, even as the present becomes fully unreal, and the Witchfinder seems to cast a shadow over the centuries to come. People like you, he says, will always be brought before people like him for judgment, people who will never believe you, or will, but won’t care. You are left with the question: How long can you walk?

Min Sang Kim, countertenor, and the ensemble Balance Campaign in a developmental workshop of Waking the Witch.

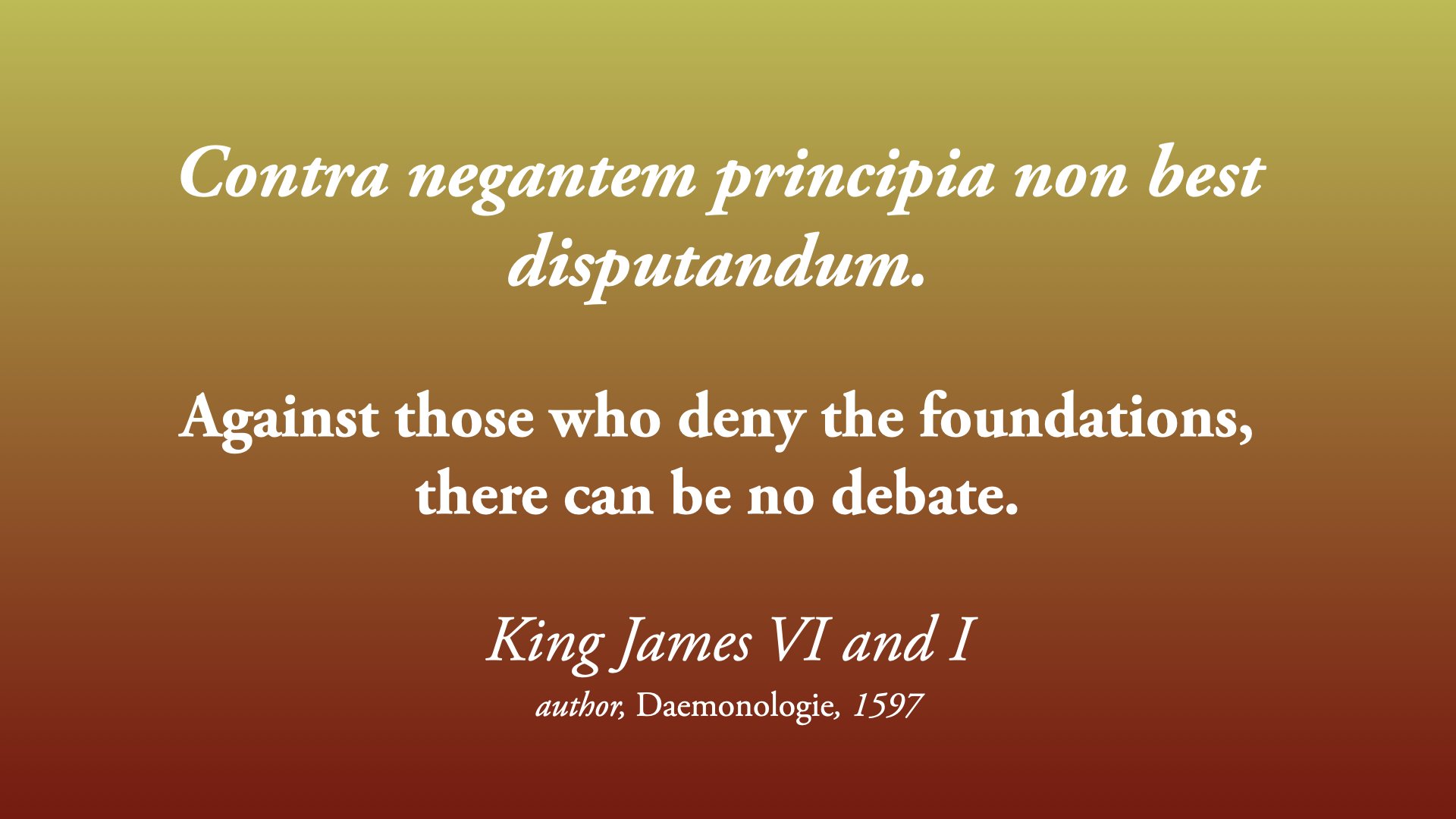

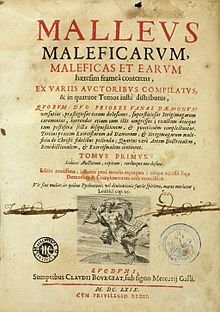

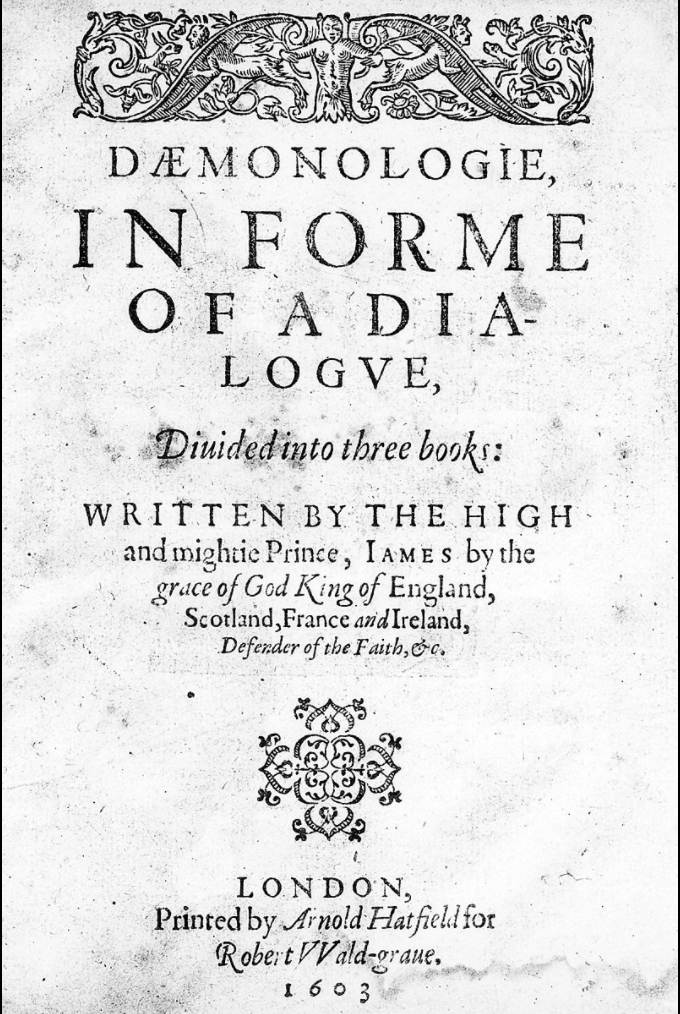

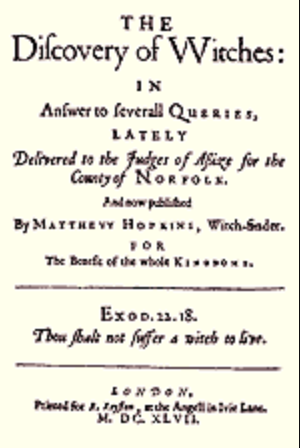

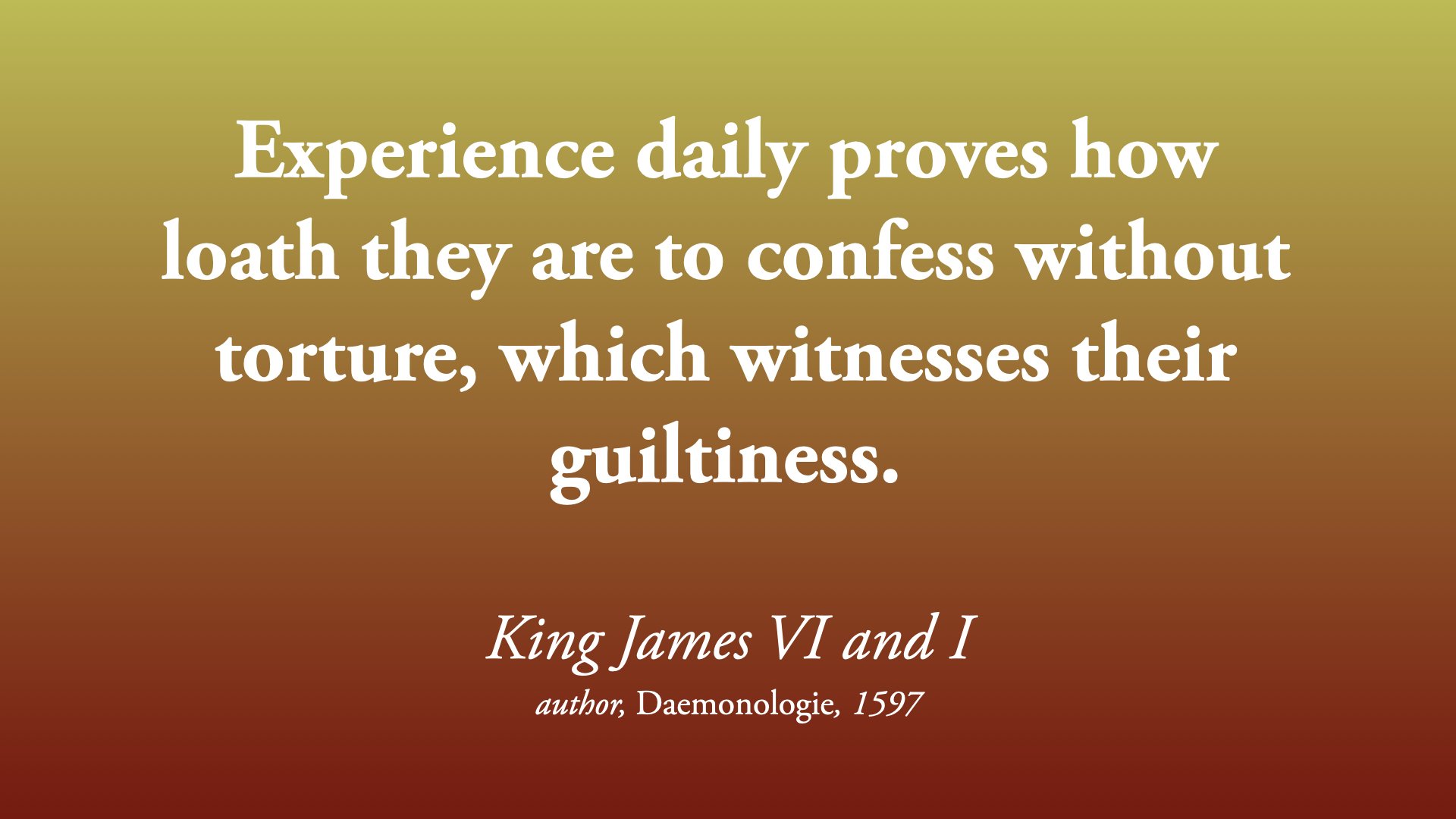

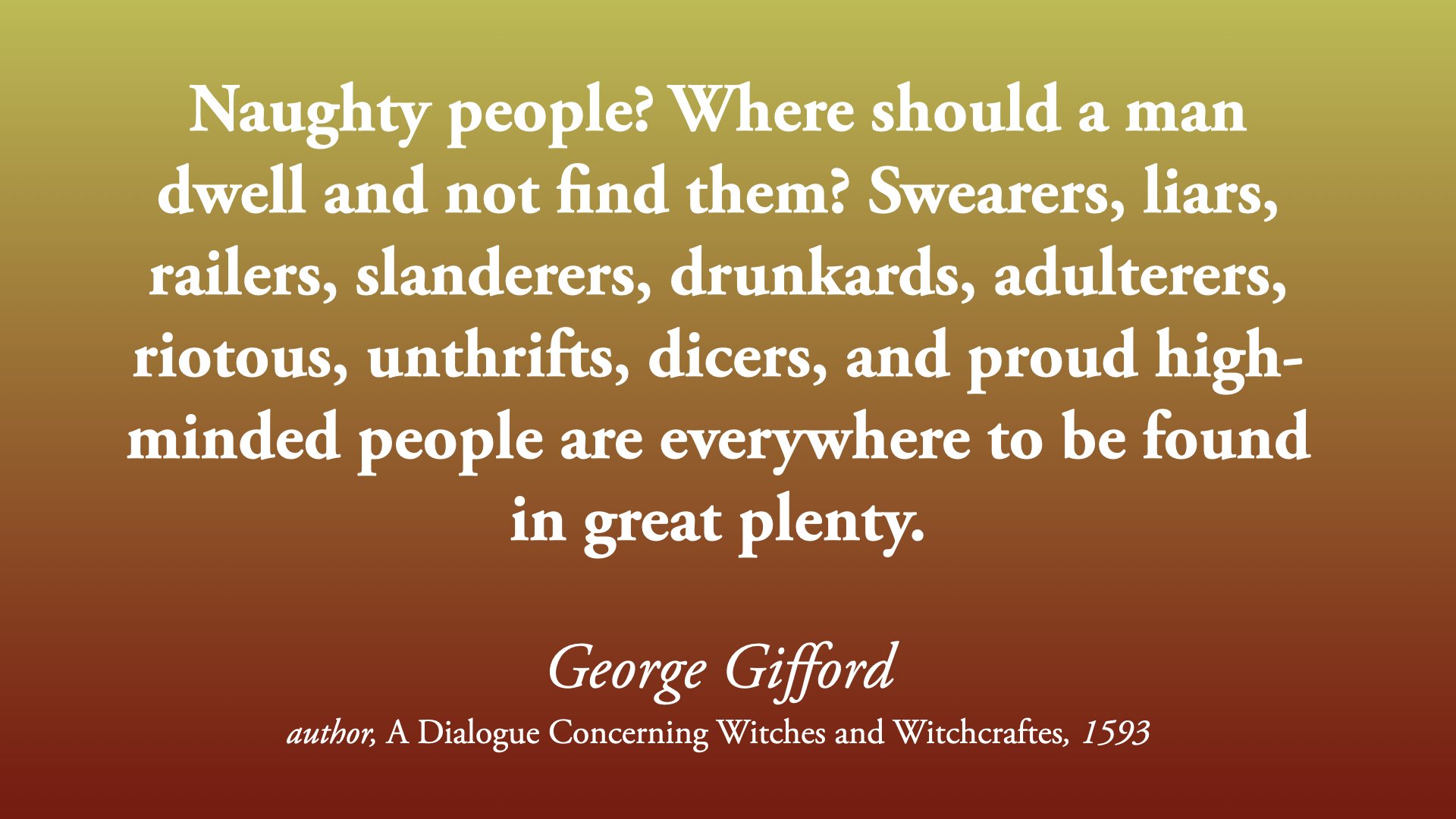

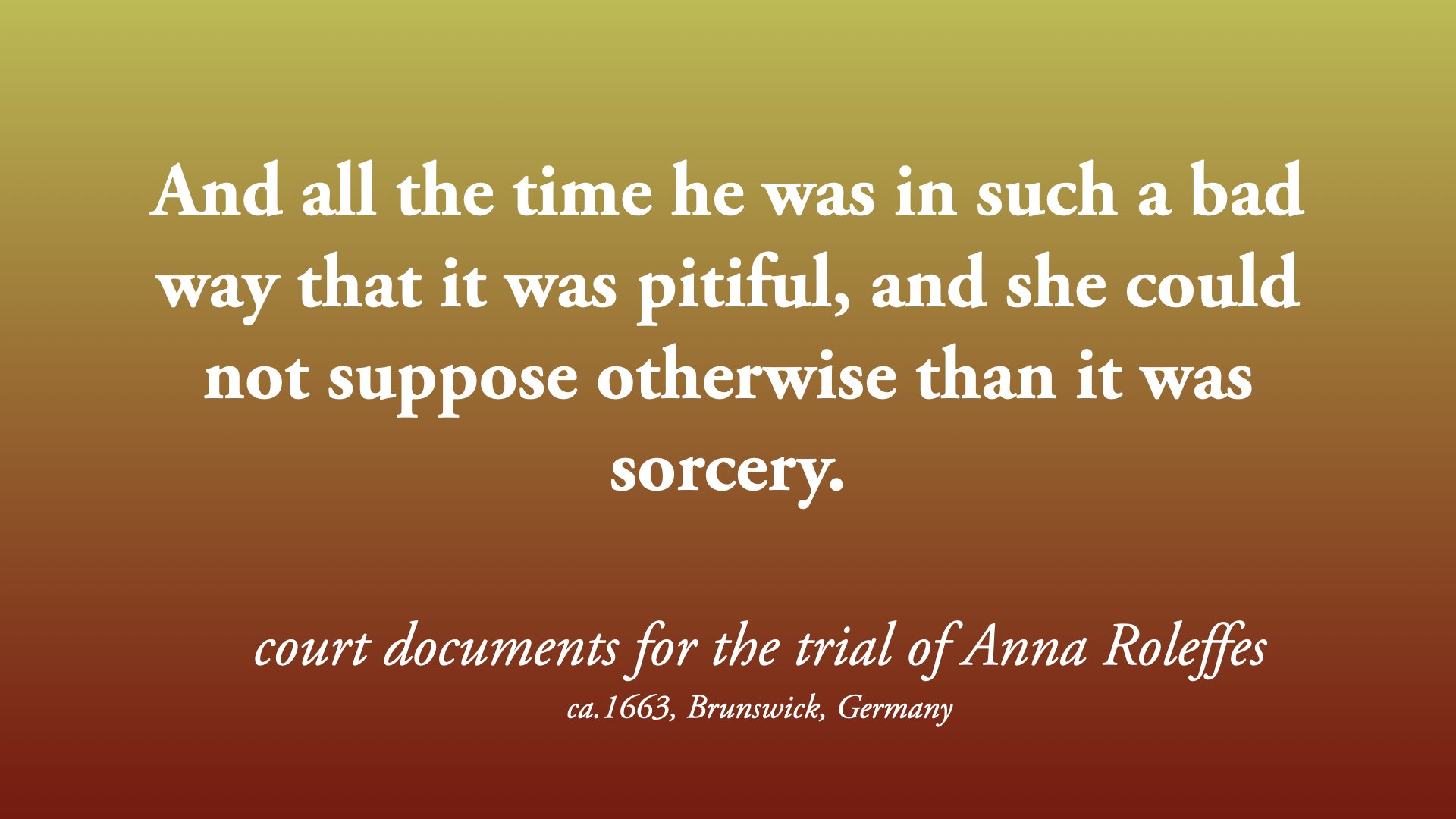

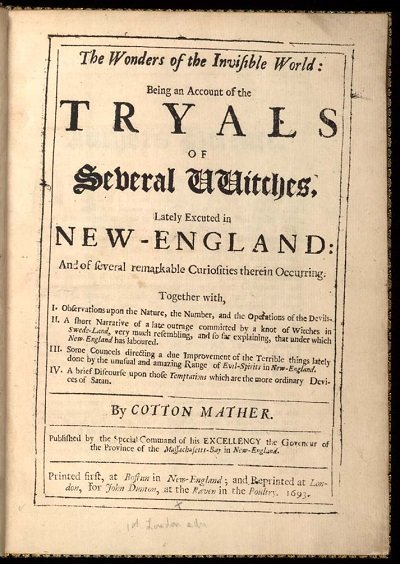

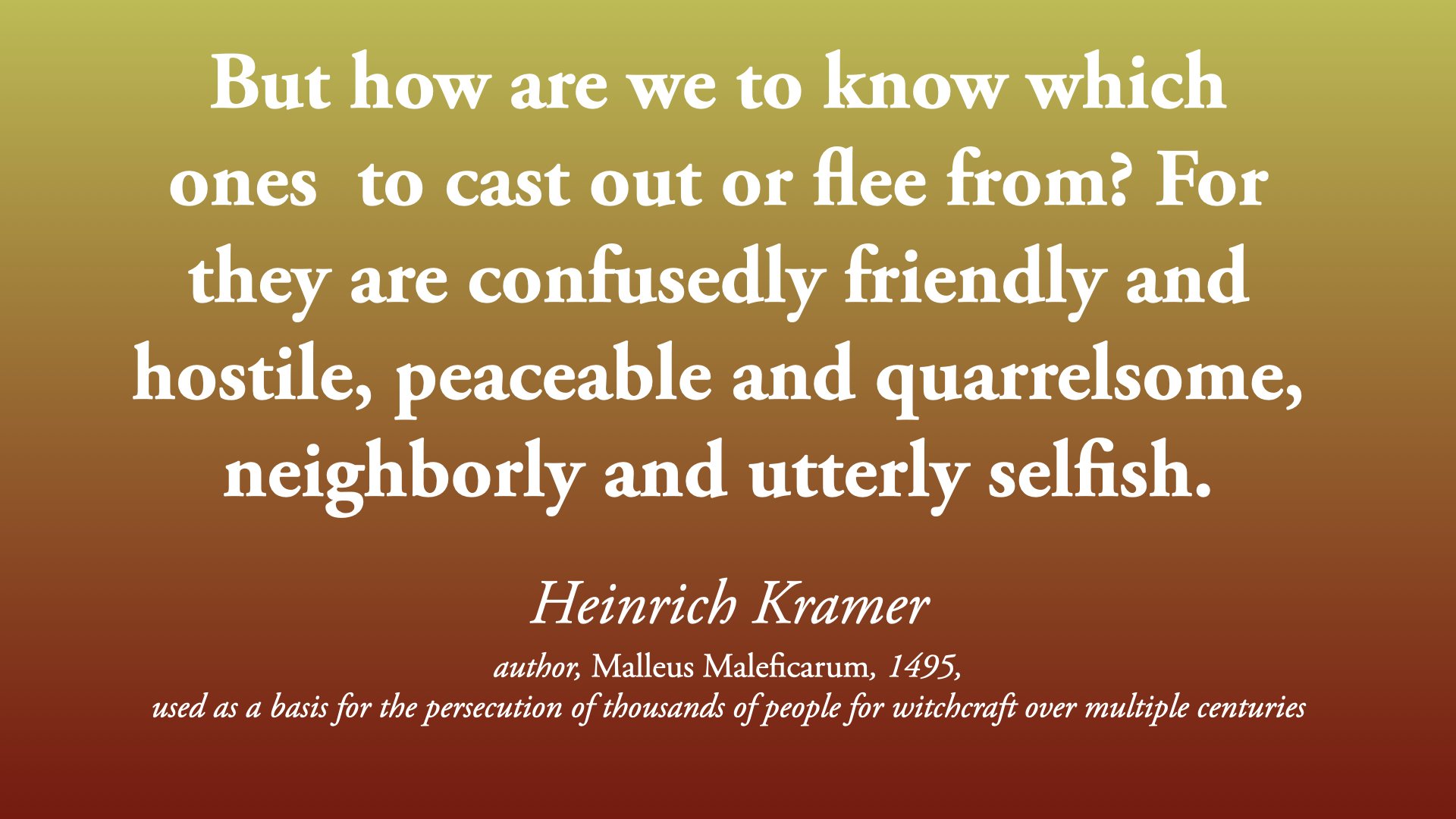

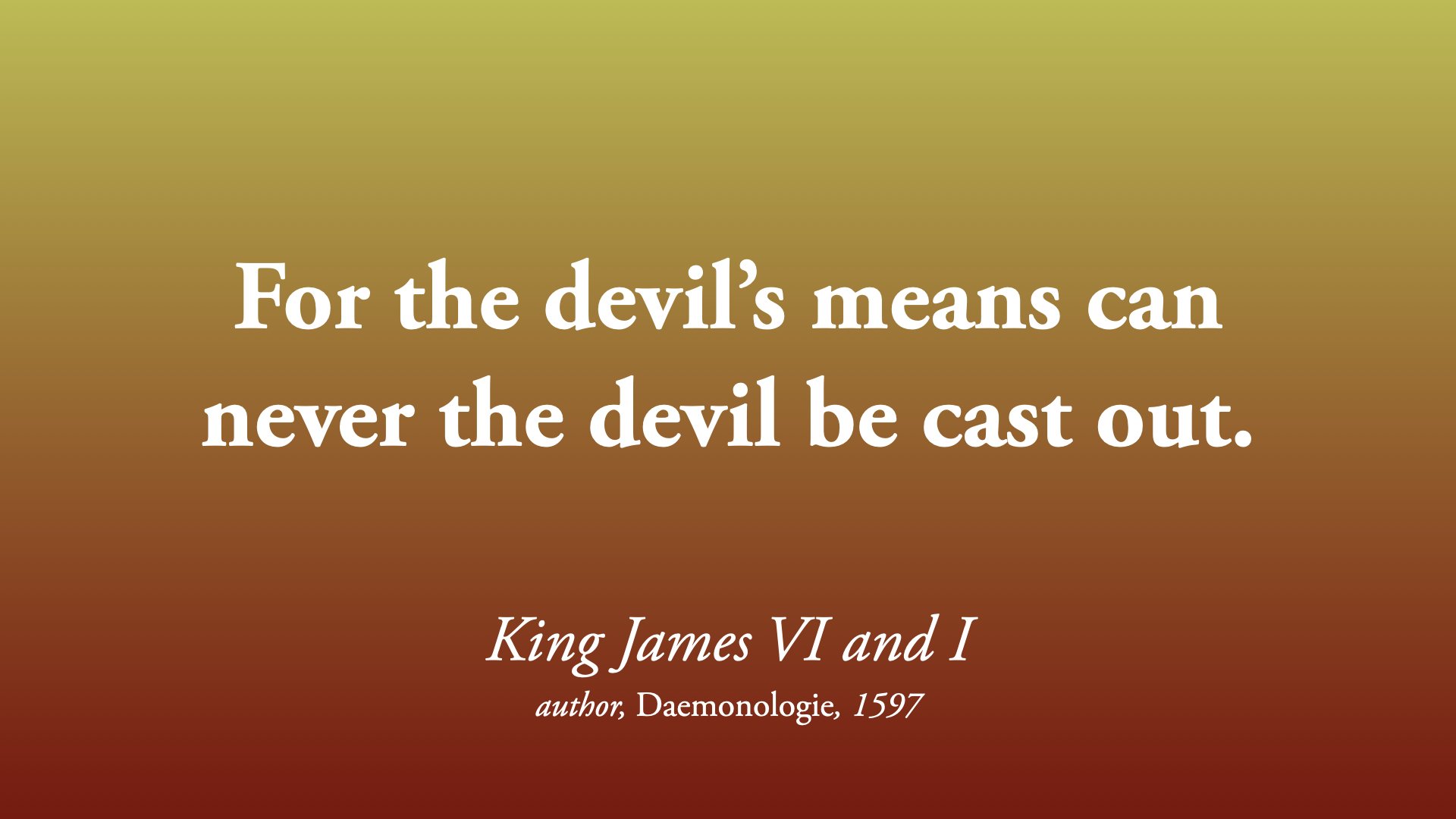

The libretto: The words and thinking of witchfinders and their successors. The libretto of Waking the Witch is derived through paraphrases and echoes of historical documents from the time of great witch panics (roughly 1450-1750 in Europe and what would become America), a time during which tens of thousands of people, mostly women, mostly poor, were prosecuted for crimes they could not possibly have committed. These sources include academic texts, pamphlets, and court documents, such as Malleus Maleficarum (Heinrich Kramer, 1487), A Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcraftes (George Gifford, 1593), Daemonologie (King James, yes that one, 1597), The Discovery of Witches (Matthew Hopkins, the self-appointed Witchfinder General, 1647), the trial of Anne Roleffes (known as Tempel Anneke, ca. 1663), and documents from American witch trials in Salem and elsewhere (mostly mid- to late 1600s). These are supplemented with the occasional quote or paraphrase from modern American leaders and political movements whose statements eerily echo the witch hunters.

Inspired in part by Augusto Boal’s forum theater, Waking the Witch asks the audience place themselves in the position of the person being questioned in order to think about how we collectively come to be in situations of widespread misinformation and fearmongering and why the most vulnerable are so often feared and blamed. And then, to consider how we can respond, what we might do as individuals and as groups to change current and prevent future dehumanization, oppression, and moral panics.

The music: Waking the Witch is meant to be appropriately eerie and spooky for its subject matter, while maintaining enough distance and sense of play to avoid being (re)traumatizing to audience mbembers. Tuneful, even catchy tonal and modal melodies are interspersed with moments of free improvisation. Like the ideology the Witchfinder espouses, the music begins in the late medieval church and ends in Americana. Styles and techniques like chant, Puritan psalmody, pastoral laments, Baroque dances, and fugue slowly turn into vamps with improvised solos, theme and variation with driving steady beats, fiddle chopping, slap bass figures, and moments that might feel like a witches’ sabbath celebrated on an Appalachian mountain. Much of the questions directed at the audience are in semi-improvised sections, allowing the Witchfinder, and later the familiars, to move through the audience, directing questions directly to them (the audience is not expected to respond; after all, the Witchfinder isn’t really going to consider anything that doesn’t fit his current understanding). Regularly, the Witchfinder repeats an invocation: Confess, confess, confess. Walk. It isn’t over yet.

The structure: Waking the Witch, while not specific to any trial, location, or time period, still follows a common pattern in witch trials: suspicions between neighbors build up over years, often aggravated by environmental or societal stressors, eventually turning into formal accusations. At that point, authorities come to initiate legal proceedings, bringing with them a fear-based theology that connected injury, illness, loss of life, and loss of property with the idea that people could be imbued with special powers from the devil: witchcraft was therefore not just a crime against the community, but against all that was holy. In times when these authorities strongly believed in witches’ sabbaths or that witchcraft was a widespread problem, individual trials could turn into panics, as the accused were forced to name accomplices.

Waking the Witch sketches out this narrative within a single interrogation session. The opera is presented as a single extended scene in thirteen movements:

I Prologue

II In the midst of the disasters

III Accusation 1: The tavernkeeper’s son

IV Accusation 2: The neighbor’s wife

V Accusation 3: The magistrate’s estate

VI The Charges

VII Think On Your Soul (Trio for Animal Familiars)

VIII Proof

IX The Contract

X I Rise

XI The Sabbath

XII In the midst of the disasters

XIII Epilogue

The piano, cello, and percussion form the accompanying ensemble, while the flute, clarinet, and violin play animal familiars. Animal familiars were believed to be demons in the shape of small animals that were given to witches by the devil as agents who could work evil magic. These instrumentalists are included in the staging, following the Witchfinder and alternating between egging him on, adding to the ambience created by the ensemble, and playfully delighting in all that is happening. The Witchfinder doesn’t seem to notice them, and it’s not clear if they are real or hallucinations.

The piece also draws from sleep deprivation for its structure. As time goes on, a person experiencing severe sleep deprivation may lose their sense of time, become highly suggestible, and experience hallucinations. In addition to the possibly-hallucinatory animal familiars, he opera incorporates the idea of microsleeps, or short losses of consciousness that might happen involuntarily during extensive sleep deprivation. Keeping people awake through “walking” was a technique used in the witch panic in East Anglia during the English civil war. At that time and place, torture was illegal, but keeping people awake for several days was not considered torture. The microsleeps appear in the opera as brief blackouts accompanied by white noise; when the scene resumes it’s clear the audience has lost an undetermined amount of time. By the end of the opera, the Witchfinder seems to be speaking across time and space, affirming that fearful, powerful men’s desire to cry both “Witch!” and “Witch hunt!” will never cease.

development

Waking the Witch began when Min Sang Kim asked Ashi to write a solo piece for him. The two hoped to create a piece that would showcase his unique talents while also becoming a piece that would give other countertenors as well as mezzo-sopranos and contraltos a chance to shine in a truly unique role. Pierrot ensemble Balance Campaign and stage director and producer Lee Cromwell signed on to advise on instrumental writing and story/libretto development.

Ashi is grateful to the Guerilla Opera Lab Writing Collective for their support with developing a new work, especially their expansive view of what operas and librettos can be. Ashi also received a Discovery Grant from Opera America as part of their larger initiatives to support women creators in opera. This award, supported by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation, was vital in supporting the workshop process.

WORKSHOP FEEDBACK

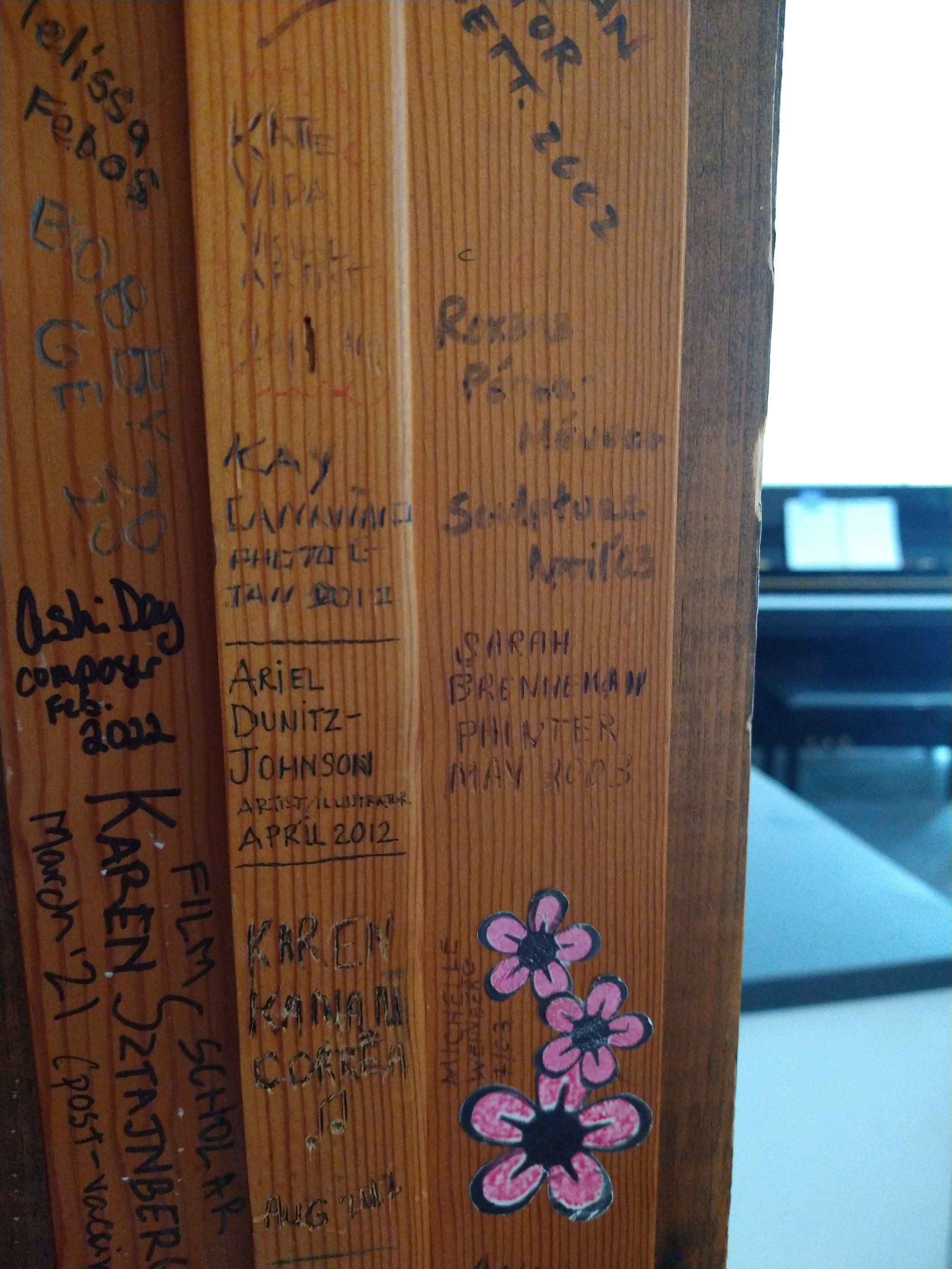

Workshops: The piece was workshopped with Balance Campaign in June, 2022, in which the first half of the opera’s music was reviewed and performed for invited guests.The piece received a second workshop with Balance Campaign in December, 2022, featuring the full score and including minimal staging. The workshop was held at the Washington National Opera rehearsal studios, with Min Sang Kim and Balance Campaign performing, stage direction and conducting (when needed) by Lee Cromwell. Workshop performances over two nights drew an audience of over 70 guests.

The Waking the Witch development team at a June 2022 workshop

Anyone considering a presentation or production of Waking the Witch id invited to work with the developmental team as collaborators OR to make the work entirely their own, with their own artistic teams. It is our hope this work can live on in multiple realizations.

Historical Context

Although witch trials happened periodically in Europe in medieval times, it wasn’t until the early modern period that trials would frequently burst into witch panics. Between 1450-1750, tens of thousands of people were executed for the impossible crime of witchcraft, with many more being tried and persecuted. While people from all walks of life were accused, the majority by far were women, especially women who were old and poor.

It is impossible to parse out the exact reasons for witch panics, but they tended to happen when societies were unstable and tension was high, such as in periods of war or drought. In addition to feelings of fear and suspicion, instability could also mean that legal proceedings were followed less strictly, or led by less trained individuals, contributing to the accusations and executions getting out of hand.

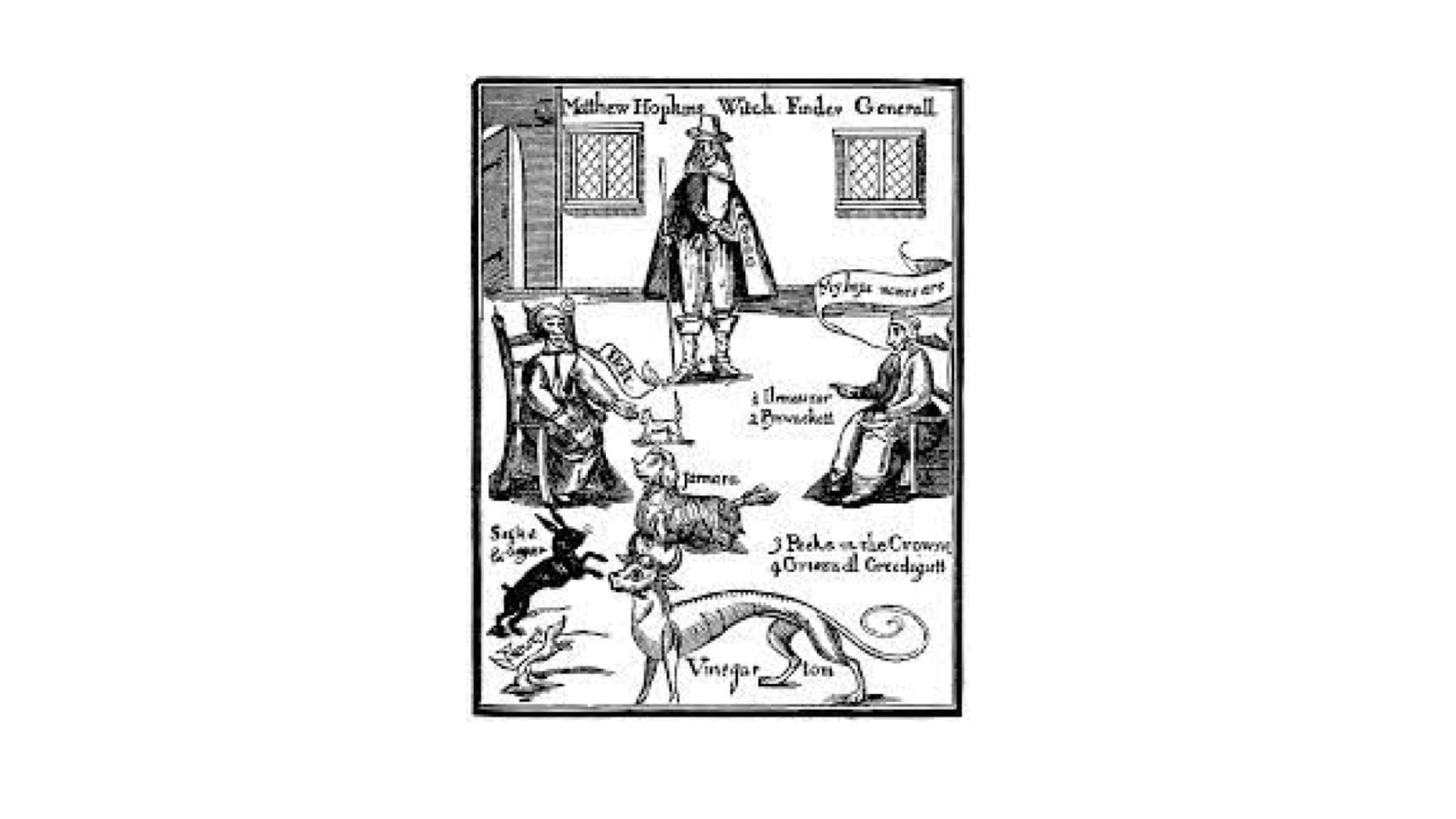

Witchfinders: A number of influential men significantly contributed to worsening the fate of suspected witches. In the late 1400s, after unsuccessfully persecuting an accused witch, priest and inquisitor Heinrich Kramer wrote the Malleus Maleficarum, or “hammer of the witches,” that, despite questionable scholarly practices, became essentially a handbook for hunting witches influencing generations. It asserted that witchcraft was not just magic used for bad deeds, but the ultimate heresy. Women couldn’t possibly have such power themselves, so it must be given to them by entering into a contract with the devil, who was always looking for ways to destroy godly societies. Witches were the ultimate traitors, and not acting alone. In addition to Kramer, others stand out: Johann Georg Fuchs von Dornheim, the “Hexenbischof” (“witch-bishop”), oversaw the death of hundreds in Bamburg. King James VI and I of Scotland and England participated in witch trials in Scotland and published a text on identifying and persecuting witches, Daemonologie. Matthew Hopkins, the closest inspiration for this opera’s main character, dubbed himself the Witchfinder General. In the chaos of the English civil war, he and his partner John Stearne offered their services—for a hefty sum—across East Anglia to search and interrogate accused witches in order to prepare evidence for trial, despite having no legal qualifications.

Waking the witch: One of the reasons witchcraft could appear to be a legitimate problem was because, due to torture, people would often confess. Likewise, torture would be used to get accused witches to name conspirators, ensuring that single cases could quickly expand into full blown panics. The scenario for this opera is most closely derived from the witch hunts of East Anglia in the 1640s. At this time, torture was illegal, but Hopkins and Stearne made use of the loophole that sleep deprivation was not considered torture. An accused witch would be kept awake and made to walk around a room for several nights without rest in a process called “watching,” “walking the witch,” or, “waking the witch,” hence the title of this piece. Whether the confessions of those who endured this process were based on hallucinations, heightened suggestibility, or just desperation to make it end, we will never fully know.

Witch trials in America: The witch trials erupted from the Christian theology of the time, which very much believed that the devil was a real and powerful threat. All types of Christians—Catholics and many branches of Protestants—were guilty of persecuting witches. These beliefs, as well as high-stakes, good-versus-evil, apocalyptic thinking, were brought to what is now the United States by these same European Christians. Witch trials began in the US, starting in Hartford, Connecticut in 1662. Most famously, the Salem witch trials of the 1690s represented a late stage witch panic, occurring in the Puritan community in Massachusetts after much of the world had begun to move on. It is possible to see the echoes of this ideology and propensity for persecution and panic across US history, in McCarthyism, the Satanic Panic, Q-Anon, and more.

More Info:

Learn more about this fascinating topic with the resources below, which have been invaluable to the creation of this opera:

The History of Witchcraft podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-history-of-witchcraft/id1239548646

BBC Radio Scotland: Witch Hunt podcast https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07rn38z/episodes/downloads

Profs & Pints online: Witches and Witch Hunts with Dr. Mikki Brock https://www.crowdcast.io/e/witches/register

History Extra podcast episode: Witch Hunters: Cynical Persecutors or Misguided Zeolots? https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/witch-hunters-cynical-persecutors-or-misguided-zealots/id256580326?i=1000552571905

PRESS

Opera America Discovery Grants for Women Composers: Press Release

OperaWire: Q&A: Ashi Day on ‘Waking the Witch’ & Contemporary Opera

Bucknell Magazine: Making Music Together: Ashi and director/libretto advisor Lee Cromwell, both Bucknell alumni, on collaborating on Waking the Witch

Listen to an interview about Waking the Witch and the future of opera with Opera America’s Opera Teens National Council here:

About the creator

Ashi Day, composer and librettist

Ashi Day’s vocally driven works explore the intersections between music and theater; strategic humor and absurdity; the interplay between the experiences of performers, audiences, and the canon; and animal songs. Her two short mono-operas, For Whom the Dog Tolls and The Green Child, intentionally provide sopranos with the rare opportunity to be playful and victorious for most of the plot, while subtly exploring who is allowed to move freely through the world. Her art songs, choral pieces, and theatrical works have been commissioned or performed by Artifice, Juventas New Music Ensemble, Calliope’s Call, Whistling Hens, N.E.O. Voice Festival, American University, Washington State University, Denison TUTTI, StageFree, District New Music Coalition, and more. She is a 2021 DC Arts and Humanities Fellow, an award granted to artists who significantly contribute to the cultural vitality of the District of Columbia.

A former elementary school music teacher, Day now manages several education programs for the Kennedy Center and the Washington National Opera. Much of her work focuses on career development for high school singers interested in opera and vocal performance.

Learn more about her work in opera and other projects at www.ashi-day.com/opera.

Behind the Scenes

The development of Waking the Witch received funding from

OPERA America’s Opera Grants for Women Composers: Discovery Grants program, supported by

the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation.

And a gift of time at the Millay Arts retreat center.